Final Writeup

This document is a final report of our Distributed Question Answering System project for the course 15-418 Parallel Computer Architecture and Programming, and we will cover the following topics in this report:

- Summary

- Background

- Approach

- Results

SUMMARY

In this project, we built an end-to-end Question Answering system with the following features:

- Distributed backend server with multiple QA instance

- Distributed computation of Question-Relation similarity with Master-Worker design

- Measure word sequence similarity with Bi-directional LSTM models

- Freebase knoledge graph visualization with Javascript

BACKGROUND

What is Freebase?

Freebase [1] is a large collaborative knowledge base currently maintained by Google. It is essentially a large list of 19 billion triples that describe the relationship among different entities.

The data is stored in structured databases where information can be retrieved using well-defined query languages such as SPARQL and MQL. In this project, the Freebase data is loaded into the Virtuoso database, and SPARQL queries were initiated during the process of generating fact candidates for each question in order to request for information about entities and relations.

System Architecture

If we were asked to find the answer for the question “Who inspired Obama?” in Freebase, we might want to take the following steps:

- Identify the question is about the entity “Barack Obama”

- Scan through all possible relations connected to “Barack Obama”

- Find the best matched relation “influence.influence_node.influenced_by”

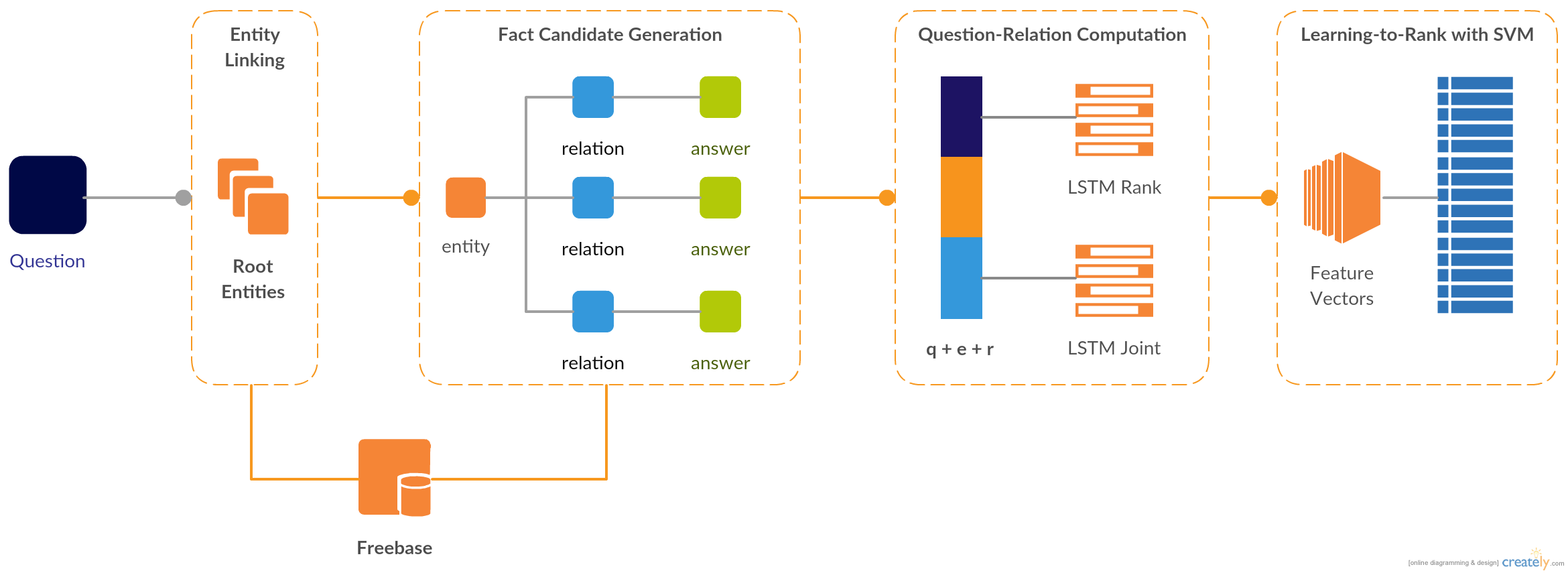

The architecture of the Question Answering system is illustrated below.

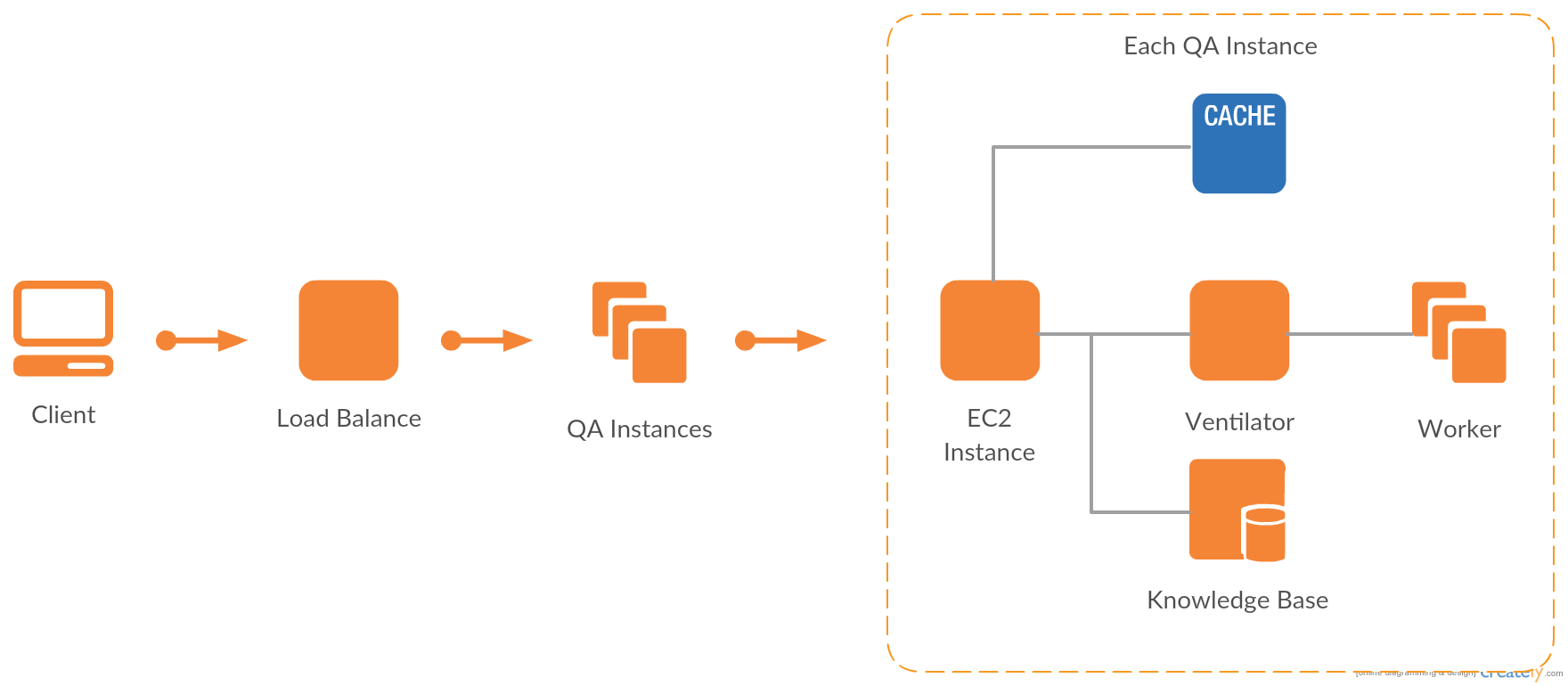

Backend Design

Upon receiving a request from client, the load balancer will assign the query question into one of the QA instances for analysis. Each QA instance has a complete copy of the Freebase system, as well as a cache for storing past fact candidates. The derived fact candidates from QA system are in the form of triple and turned over to the ventilator, the primary task scheduler, to be further assigned in a distributed network.

APPROACH

Fact Candidate Generation

We used the Entity Linker in the Aqqu system [2]. During the entity linking process, each subsequence of the query text is matched with all Freebase entities that have name or alias that equal to . These Freebase entities are the root entities recognized from the question, and the popolarity score computed with the CrossWikis dataset [3] is added to the feature vector in the purpose of measuring entity linking accuracy. The CrossWikis dataset was created by web crawling hyperlinks of Wikipedia entities, and it could be used to measure the empirical distribution over Wikipedia entities. For entities that are not covered by CrossWikis, we only consider the exact name match.

For example, the input question “who inspired obama?” will produce possible subsequences such as

in which the subsequence “obama” match the alias of the entity “Barack Obama” with popularity score of .

After identifying the root entities of the question, we can generate the list of fact candidates by extending the root entities with all possible outward edges (relationship) in Freebase. Some example fact candidates generated from the root entity “Barack Obama” are illustrated in the following figure.

Relation Matching with Bi-directional LSTM

Long Short Term Memory networks – usually just called “LSTMs” – are a special kind of RNN, capable of learning long-term dependencies. The motivation for using LSTM is that LSTM has been proved to be quite effective when solving machine translation problems, and matching relations can be considered as a form of translation.

Each Bi-directional LSTM model is trained pairwisely. Consider there are total of fact candidates for the query . We pair them up and get a total of training instances for query . For each training instance pair , the corresponding label will be either or depending on which fact candidate has higher measure. The measure of a fact candidate is computed by the precision and recall of the answers compared with the gold answers provided by the dataset. The pair of fact candidates will then be fed into a pair of identical Bi-directional LSTM model ranking units, and the ranking score of each fact candidate can later be computed by the ranking unit after the training process.

The query text and the fact candidate components (subject, relation, object) are parsed into word tokens or tri-character-grams as described in [4]. For example, the text “barack obama” will be translated into the following tokens,

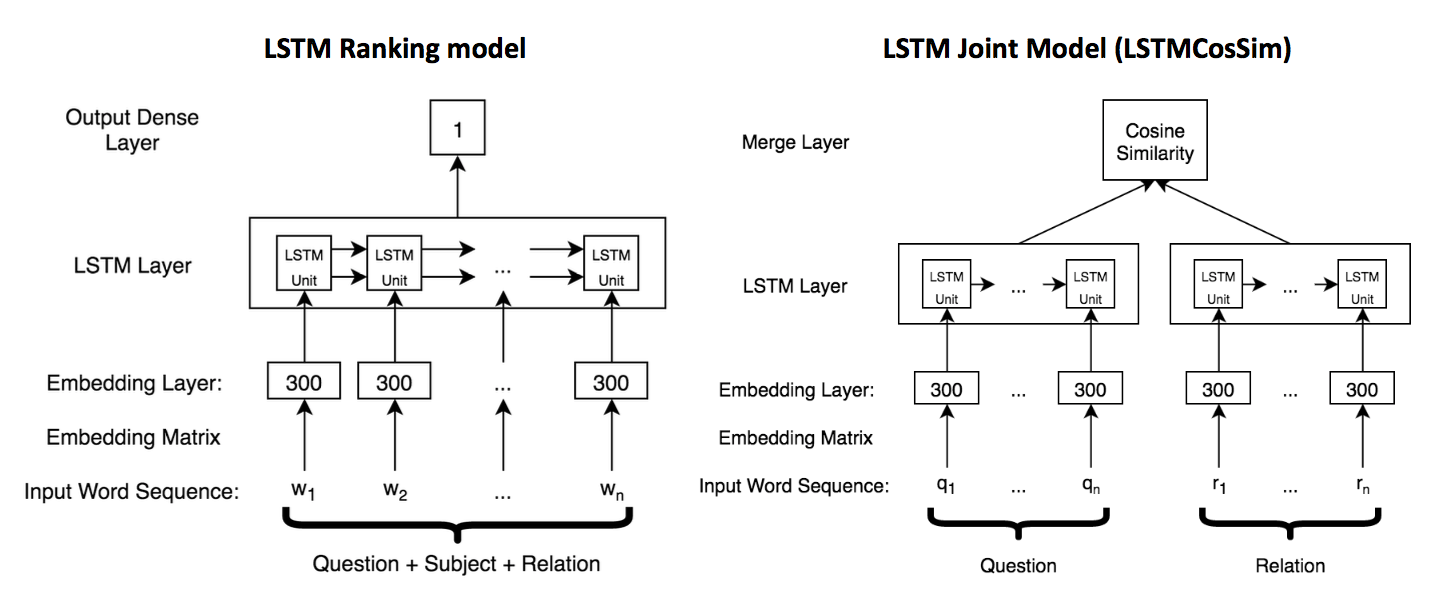

These tokens will be input to the embedding layer of each model. The structures of the ranking units for both deep learning models are illustrated below.

In the LSTM Ranking model, the ranking unit will take a single sentence as input consists of the question, subject and relation tokens. With each token input into the embedding matrix, a long list of embedding vectors is passed to the Bidirectional LSTM layer with output size of 1, so that the output of the LSTM layer will be the ranking score of the input fact candidate.

Different from the LSTM Ranking model, the LSTM Joint model will separate the question and relation tokens as separate input instead of combining them together. The corresponding embedding vectors are passed to two separate Bi-directional LSTM layers, and the final ranking score of the fact candidate is the cosine similarity calculated from the output of the two LSTM layers.

Distributed Question-Relation Similarity Computation

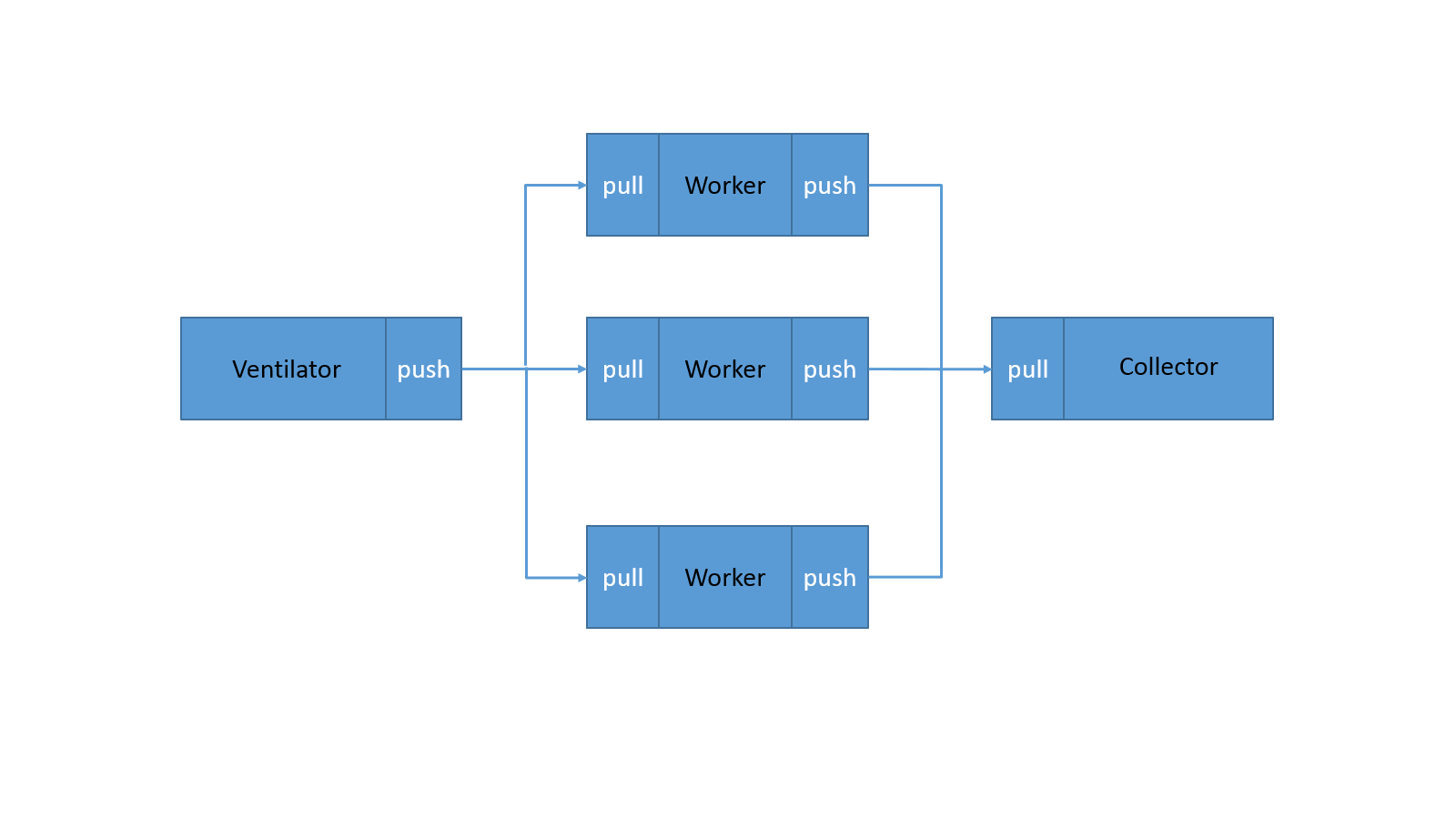

Given the large amount of Freebase triples to be searched, it provided our group sufficient motivation to distribute the computation to multiple nodes across the network. Each query request can be packaged and sent to a pool of workers, such that data-parallelism can be leveraged upon. In order to achieve this goal, we eventually decided the following structure:

-

We adapted a three-level pipelined structure. The ventilator is the producer of the queries and is responsible for packaging the data and sending jobs to workers. The workers are the intermediate consumers of the pipeline and are accountable of the most CPU intensive work. Instead of sending the result back to the producer, the workers will send the result downstream to a common result collector to avoid excessive communication traffic on the producer side. It also reduces contention for physical resources inside the ventilator. If further iterations are required, the message could be sent back from result manager to ventilator in a message batching manner, which will also be illustrated later.

-

In order to distribute the data efficiently, we adapted asynchronous socket programming that could be deployed to multiple machines with ease. Given the few dependencies on the queries, as well as the flowing query processing pattern, it makes an asynchronous queue structure preferable. Additionally we used the ventilator to dynamically monitor the queue size of each worker to maintain load-balancing. Requests on socket are scheduled in a round-robin manner out of the concerns of simplicity and unpredictiveness of exact location of the message (ventilator’s buffer, wire, worker’s buffer, to name a few). Neither shared memory nor pipe structure was considered in this scenario, as we are distributing the requests across the network.

-

Lastly distributing the data has the additional potential benefit of allowing queries too large to fit into one CPU’s memory to be used, which could be useful when larger knowledge base is incorporated into our application.

RESULTS

Evaluation Data: WebQuestions

WebQuestions benchmark contains 5810 questions in total, and all questions were created by the Google suggest API. For training and testing purposes, the dataset has been partitioned into two segments where 3778 (70%) of the questions will be used for training and 2032 (30%) of the questions will be used for testing. The queries in WebQuestions are less grammatical and are not specifically tailored to Freebase, which make the questions more complex and more difficult to answer for Question Answering systems. The reference answers for the questions were obtained by crowd-sourcing, which might introduce additional noises during system evaluation.

The performance is evaluated by the average precision, average recall and average measure of the retrieval answers across all questions in the test set. The average measure of the dataset is computed as following,

Accuracy

| System | Average Recall | Average Precision | Average F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQQU [2] | n/a | n/a | 49.4% |

| STAGG [4] | 60.7% | 52.8% | 52.5% |

| AMA | 57.2% | 39.6% | 38.2% |

Speedup

The following plot is the response time of processing each question in the WebQuestions test data set. Please zoom in to examine the data.

We compare the response time across 4 experiment setups:

- Sequential

- Multi-threading on single machine

- Distributed computation on 8 machines (distribute by model computation)

- Distributed computation on 8 machines (distribute by fact candidate chunk size of 40)

The following plot shows the average response time for each experiment setup.

We find that the average response time for the multi-threading setup is even worse than the sequential version. This is due to the fact that the computation of the similarity scores with the LSTM models is highly CPU-intensive, and distribute the computation to multiple threads only increases the overhead of the program for questions with small amount of fact candidates. However, when we examine the data closely, we can see that the multi-threading version has reasonable speed-up for questions with large number of fact candidates.

For the distributed computation on 8 machines by fact candidate chunk size of 40, we reached an average speed up of x compared with the sequential version.

FURTHER IMPROVEMENT

Previously we aimed to parallelize SVM as one of our goals of the project. However given the limited time and the fact that we have derived our knowledge base from training algorithm, we did not manage to provide a paralleled solution to SVM learning at this point in time. The classification process of SVM is derived from a simple dot product calculation and is trivially parallelizable given the vectors. Therefore we omit the part of accelerating SVM through techniques learnt from the class in our final support. In one of the paper of Joachims, the author described an algorithm that accumulates the number of positive and negative occurrences, which will result in computations per constraint in the SVM problem instead of . While the algorithm poses more dependencies between iterations within a loop, it would be an interesting idea to attempt parallel techniques on this faster algorithm.

WORK DISTRIBUTION

Equal work was performed by both project members.

REFERENCES

-

K. Bollacker, C. Evans, P. Paritosh, T. Sturge, and J. Taylor. Freebase: A collaboratively created graph database for structuring human knowledge. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD ’08, pages 1247– 1250, New York, NY, USA, 2008. ACM. ↩

-

H. Bast and E. Haussmann. More accurate question answering on freebase. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, CIKM ’15, pages 1431–1440, New York, NY, USA, 2015. ACM. ↩ ↩2

-

V. I. Spitkovsky and A. X. Chang. A cross-lingual dictionary for english wikipedia concepts. In N. C. C. Chair), K. Choukri, T. Declerck, M. U. Doan, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, A. Moreno, J. Odijk, and S. Piperidis, editors, Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’12), Istanbul, Turkey, may 2012. European Language Resources Association (ELRA). ↩

-

W. Yih, M. Chang, X. He, and J. Gao. Semantic parsing via staged query graph generation: Question answering with knowledge base. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of the Asian Federation of Natural Language Processing, ACL 2015, July 26-31, 2015, Beijing, China, Volume 1: Long Papers, pages 1321–1331, 2015. ↩ ↩2